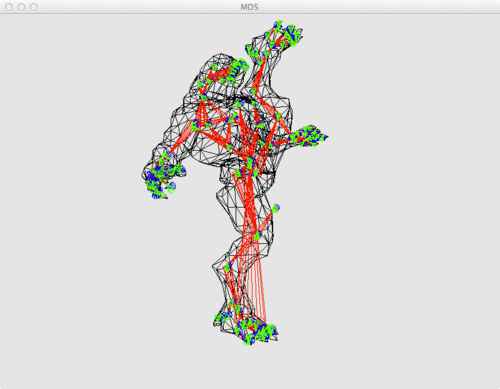

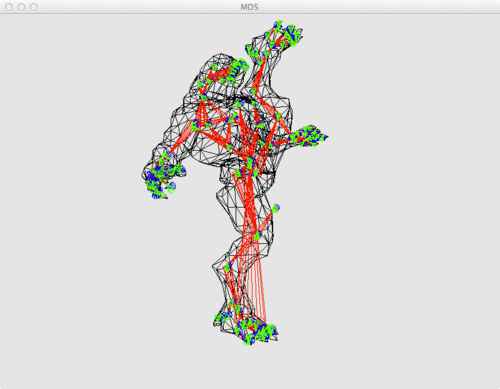

Skeletal Animation is annoyingly hard! To be fair though, its the real crux of this whole gig. Getting the skinning working right, the bones all moving properly and the whole thing being easy to use is 90% of this project. So I’ve been spending a fair bit of time with the MD5 model format.

It’s an elegant, yet deceptively smart file format. It can be human read, compressed easily and contains all the data in an organised format. There are a few subtleties to it however that can trip you up.

The first is the American system. Y is Z and Z is Y. I have no idea why Americans do this, especially since we talk of Z depth. Anyway, its easy to work around with a single matrix but its an extra level in the process.

That’s the problem with skinning; there are a lot of simple steps - a hierarchy of steps - that can make the whole thing come crashing down. My first mistake was an incorrect matrix transposition. I’d thought it was sorted until my translations stopped working.

The second was related to the relative transformations one needs to build. In the MD5 format, or indeed, any format, one needs to first find the bind pose, which is easy enough to compute. The MD5 format actually builds the vertex positions and bind pose from the weights and joints rather than list them explicitly. In addition, unlike any other format, the MD5Mesh uses positions with its weights. Im still not sure why this is, but apparently it leads to faster CPU skinning. This is not much use to use now as we do GPU skinning these days.

So how do we get the relative transforms? Well, you take the parent orientation and position and get the difference right? Wrong! You also need to unravel the position by undoing it’s movement due to the parent joint’s rotation! Why do we need these relative transforms? Well, because skeletal animation is hierarchical and any transform applied to, say, a thigh-bone, should affect the knee bone and shin bone etc etc. All we have is the absolute position in space of the joint and the vertices at that point, so we need to do some computation.

With that all done, we then need to compute the matrices we send to the shader. We take each bone in order (parents come before children - we need a sorted list of bones - the MD5Mesh is already sorted) and take the relative rotation and position (both can be modified) and add it to the parent’s cumulative rotation and position. This new value becomes that bone’s cumulative value (or global value if you will). We continue down the tree till there are no more bones.

The final step is to multiply by the inverse bind pose matrix. This is something we can work out once and save. Its the matrix that effectively undoes the transformation of the bind-pose. So we start with the bind pose, go back to no bind pose using the inverse bind pose matrix, then back again with our modified, or non-modified set of new matrices.

Sound simple? It is really but it’s made much harder by having many moving parts (ahahaha!) that can and do go wrong. Small things like making sure all the Quaternions are unit, that the W component is computed properly and that your visual aids are properly aligned - it all takes time, and a lot of time if any one of these things are wrong. Glad to say, it’s all there and working. Next step, matching this set of bones to the ones from OpenNI and find a suitable model.

Sintel is the first model I chose for the game. This is because she is designed to be used in Blender, is free and is well rigged. Probably too well rigged if I'm honest. The idea was to extract the bones I didn't need in order to convert her to an MD5 format for the game. In the end, I had to remove all the armatures and create the texture weights, skins and bones myself.

Weights refer to the amount of influence each bone has on a vertex. A vertex can, in theory, have many bones attached to it, and Sintel certainly does, including several for the face. This is too many for a normal game (although probably not these days if I'm really honest). In my case, we just need these bones that map to the OpenNI derived positions. This is quite easy to do in Blender. When you create a bone, you can tie it to a set of vertices and create the weights auto-magically. Just check them over first in case any are out of whack.

After a lengthy process of export, retry, export, try again, Sintel is ready for gaming. With no hair or eyeballs, she does look a little spooky but since we are looking from the first person, I suspect it will be fine!

In the end, however, it was deemed that less caricatured model should be used, and preferably a male one as the majority of patients at the clinic will be male. Originally, I thought Sintel was quite androgynous but playing the game for a few minutes changes that. In addition, the gloves probably would have created some cognitive dissonance.

So OpenNI2 actually makes things easier (when you remember that GLM takes its quaternion arguments in alphabetical order for some reason :S !) I’m basically just working with the arms here because I’m lazy and I have a wheelie chair. But the same skeleton used in the MD5 is working great with the OpenNI NiTE2 drivers. So now we just need to map the two together and viola!

Its been a short while since the last update but at last, we have Oculus support and full tracking of the body. This video shows the warped view of the rift and me moving my hands around. The tracking is much better in OpenNI2 and I feel that the MD5 format is much simpler and easy to work with than FBX. So far, so good! Quite pleased with the result. Now its just the case of getting everything together with a nice user interface.

Multiple OpenGL Contexts and windows is supported by GLFW out of the bag which is great news. What we actually need for Phantom Limb however, is the UX on one screen, and the Oculus on the other. GLFW is great at targeting monitors and what not, for full-screen display so the oculus side of things is sorted. We need to provide for the buttons and widgets and other such controls.

QT isn’t bad but it’s very heavyweight. Under Linux (and Portable Python too), I prefer to use GTK (gtkmm specifically) as it’s often found on most distros and isn’t too heavy. Its interface is fairly simple and it’s well documented.

Shoe-horning this into Seburo was a bit tricky however. I’ve spent the last couple of days re-factoring a load of code, but now it’s much tighter and works a treat. When Phantom Limb starts up, our Windows are loaded and they are all in the right place!

Wavefront OBJ is a venerable format. It’s been around for a while and a lot of programs support it. I figured this would be the format to use for working with the Geometry of the room we end up placing our participant in.

OBJ has a simple structure that Wikipedia covers quite well. However, it’s structure is very anti-modern-opengl. What I mean is, you can’t know how many vertices or faces you have before you read the entire file. In addition, rather than actual vertices, you have indices into values per face. This means you can have a face that shares a position or two with another face, but these positions have different normals or texture co-ordinates, thus you can’t rely on a position being a unique vertex. You have to actually generate your own set of unique vertices.

It took me a while to figure out what was going on here. Thanks to the C++ STL, I used a set to record the indices into these values. I figure if a point in space has a unique combination of position, normal and texture co-ordinate, it is a unique vertex and therefore can be created and pushed onto our graphics card. Otherwise it is shared.

This means creating an entire set of new indices. In addition, to make things even harder, OBJ supports faces with any number of vertices >< This is deeply annoying as any GFX programmer knows that triangles are king (yes, I know artists love quads but you know what, they are wrong! :P ). There are good reasons for this but Wavefront didn’t get the memo. Programs like Blender understand this and will triangulate for you. I looked at the spec and it turns out that triangle fans are how OBJ represents larger faces, so I decided to go with that. It seems to work thus far.

Reading the materials is quite easy. A material typically means a separate draw call in GFX as, more than likely, uniforms will need changing and a different set of textures will need to be bound. I divide up the OBJ model, not by groups or objects (as the spec mentions) but by the material it has. All triangles with the same material are contained in the same vertex array object. This keeps draw calls down and texture binds / shader changes down as well.

With all that settled, the final hurdle (aside from testing, testing and more testing) has been overcome. Time to take this program into the real world!