One of the things you don’t find a lot of, is how people organise their graphics engines or similar. I’ve begun reading up on the Doom3 engine but it’s quite extreme, or rather, quite a lot to take in at once. Im concerned with how things like three.js, Cinder, or OpenFrameworks deals with the problem of the graphics Pipeline.

Computer graphics has a pipeline and it has ways of doing things, especially with OpenGL. So really, there should be a fairly standard way of taking data from your CPU and throwing at the GPU with all the shaders and textures it needs. Turns out this is quite a hard task and it’s something I had to battle when I made CoffeeGL. I’m not a fan of scene-graphs but I do think there is something in encapsulating the data together with some hierarchy. Assuming we have dealt with our geometry (which is the subject of the next post) how do you deal with transformations, cameras, geometry and shaders all together?

I settled on the idea of a Node class. A Node has a minimum of a matrix; it represents a co-ordinate system or a position and orientation in space. It can have other things attached such as a camera (changes the matrices in the shader) and/or a shader, texture, geometry, etc etc. To facilitate this in Javascript is quite easy, but in C++ its another matter. I created a NodeBase class and created several subclasses; one for each item that can be added to a Node. When I create a Node (a implicitly shared object by the way) I can add a Shape, a camera or whatever to it. When I do, a pointer to a new node is placed inside the linked list within Node, called bases.

This linked list is ordered. The reason is that geometry should always be the last thing to be drawn, and the shader needs to be the first thing ‘drawn’ (or in reality, bound to the current context). This approach started off as the Decorator pattern but quickly changed into something more suited to this situation. Now, Nodes can have children in the classic, tree like way. In addition Nodes can appear in many places and because everything that is added to them is an implicit shared object, I can add the same camera to different nodes or the same texture to different nodes, in order to create my scene.

Here in lies the problem I was having for most of the day. If a parent Node defines a Camera, for example, and then a child Node defines a camera, what should happen? Ideally the camera in child Node should override the parent, and indeed it does. Thats fine, but what about lights? What about the Model Matrix? The Model matrix is the matrix used locally for any geometry, lights or what have you. This needs to be multiplied down the hierarchy in order to work. This means a child Node’s matrix needs to be a combination of its own local matrix and its parents’ matrices. So what do you do?

I remembered the stack data structure - ah classic computer science! All the NodeBases that contain the matrix have a static vector that represents the stack of matrices at this point. When we walk along the tree, we multiply the current local matrix with the last thing on the stack. We then add that result onto the stack. When we come out of our recursion, we pop the value off the stack. Job done!

To present the data to the shader, we use the ShaderVisitor. This is a static class declared only once. It has one job which is to have it’s templated sign function called by a NodeBase. When this happens, it calls the glUniform functions to pass data to the currently bound shader. This is almost identical to the Visitor pattern and allows me to make the correct OpenGL calls based on the type of the data being passed using templated functions.

I use a similar approach with CoffeeGL only I create a pseudo -Node that is a collection of all the data collected as we move down the tree.

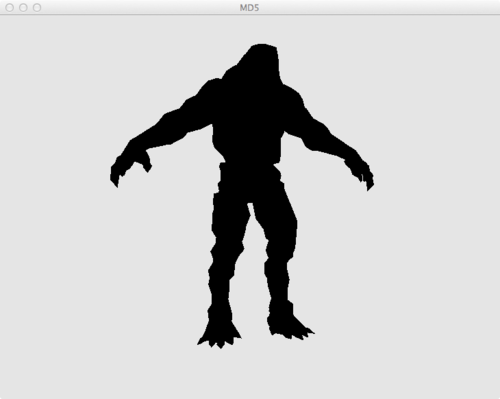

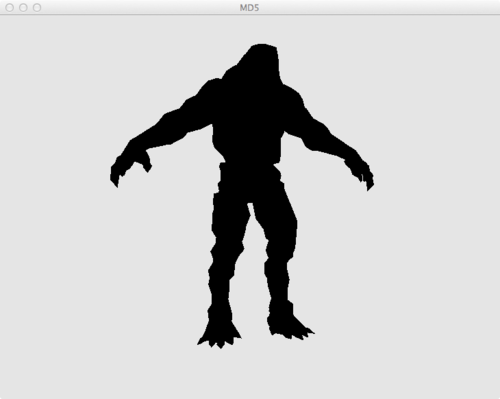

Our hell-knight model is looking a lot more cheerful now! If cheerful is the right word :S Rather than use the predefined vertex positions, this monster is calculating the vertex positions on the fly, on the GPU itself. In order to do that, we pass a load of values to the vertex shader and ask it to work out the positions for us. This is classic Vertex Skinning on the GPU.

Trouble is, the FPS is a little slower than I’d like, though I’ve no doubt it’s faster than doing it all on the CPU; we’d have to upload fresh data to the GPU in the form of vertex arrays and that is not pleasant. Still, there is room for some changes. I had a lot of issues with this program because there were a few things I was unaware of:

glVertexAttribIPointer

layout (location = 6) in vec4 aVertWeightPosBias[6];

So, the former sets a pointer into a block of data (or a bound buffer really) and matches that up to the location parameter in the vertex shader. However, everything in GLSL is aligned on a 4 float basis, or rather, 4 x 32 bit values. So a vec4 or a vec3 takes up one block. A float[4] array takes up one block, etc etc.

Since all my previous blocks were 4 x 32 in size, I never noticed my mistake till I got to skinning. If you have an attribute that is larger than a block - like, say, a matrix - then you need to make it cross several blocks. This means calling…

glEnableVertexAttribArray

…for each block that you need (4 in the case of the matrix). Once you have done that…

layout (location = 0) in mat4 aMatrix

layout (location = 4) in vec aVec

… your layout calls need to match these blocks. As aMatrix takes up for blocks, aVec must start at position 4. Finally, you must call…

glVertexAttribPointer(0, 4, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, sizeof(Vertex3Skin), reinterpret_cast<void*>(offsetof( Vertex3Skin, w) ) );

glVertexAttribPointer(0, 4, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, sizeof(Vertex3Skin), reinterpret_cast<void*>(offsetof( Vertex3Skin, w) + 16 ) );

glVertexAttribPointer(0, 4, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, sizeof(Vertex3Skin), reinterpret_cast<void*>(offsetof( Vertex3Skin, w) + 32) );

glVertexAttribPointer(0, 4, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, sizeof(Vertex3Skin), reinterpret_cast<void*>(offsetof( Vertex3Skin, w) + 48) );

… as we are packing our matrix into 4 separate vertex blocks. The OpenGL manual hints at this, but this was largely trial and error to get this far.