It's often been said that the best ideas happen in pubs. Being slightly inebriated and talking with people you like helps form ideas and makes things happen. This project starts with me attempting to learn Middle-English in a pub by speaking it aloud, like a child would, syllable by syllable, while an eminent historian giggles. Im excited because I'm a space nerd and there is computer graphics space programming to be done!

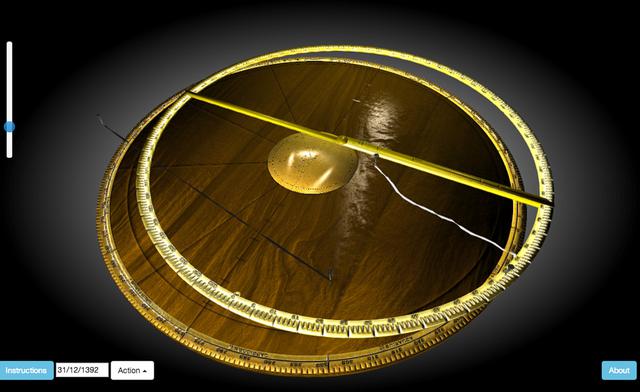

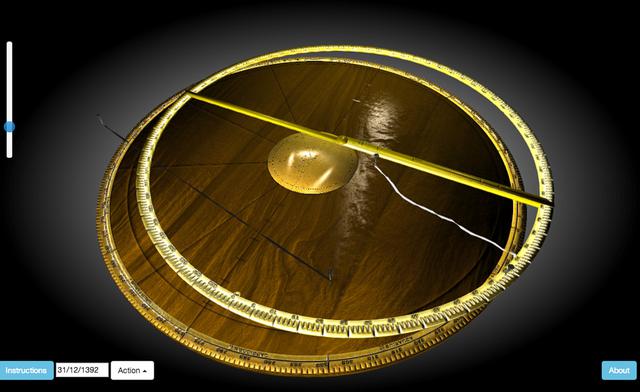

The Equatorie can be considered a sister instrument to the astrolabe. Unlike the astrolabe however, the Equatorie measures the location of the planets as oppose the stars and constellations. It was thought to be first mentioned by Chaucer, though this is now considered unlikely. The original design is based somewhat on Ptolemaic theory, the classic Epicycles upon epicycles approach.

I was approached by The Whipple Museum at the University of Cambridge to help build a 3D representation of the Equatorie as part of the digitisation of the original manuscript. I was teamed up with a lovely historian Seb Falk, who you may have seen running the London Marathon as the London Gherkin. Together, we got cracking.

Seb had already made quite a lot of head-way in working out how the device was supposed to operate. Digging around the museum stores, he had managed to find a model of the Equatorie, created in the 1950's by a chap called Price, who wrote about the Equatorie at great length. This giant model is quite difficult to use and indeed, would not have been possible to build in the 13th century. Seb set about re-creating his own version in MDF, getting a better understanding of the operation in the process, including correcting some inaccuracies in Price's original model.

With the instructions in place, I set to, with some CoffeeGL. I'd decided, early on, that this was the perfect opportunity to try and get my own WebGL libraries into shape. I'd toyed with the idea before but hadn't really had a compelling reason, aside from learning. I've used other popular WebGL libraries and simply hadn't seen any point as they never scratched the learning itch I've had.

The Equatorie is made of a few small parts, each with interesting challenges that are not immediately obvious. The main sections are the base, the label, the epicycle and the two strings. The base has a movable plate mounted in the center and there are several markings on all the major elements. This presents the first problem; scale. In the original object, scale is a major issue. It's quite hard to maneuver a large piece of brass accurately and depending on how small and taut your string is, you'll have trouble taking accurate readings. Scale is still an issue with the virtual model. You'll need a texture that looks good up close and far away, with potentially quite large gaps of 'not very much' in between the areas of interest.

The next challenge are the two strings. Critical to the operation of the Equatorie are the two strings that allow for measurement. They are attached to two pins that are placed in the various holes on the center plate, the epicycle and elsewhere. Originally, I had modeled these in ammo.js, an llvm port of bullet physics. I didn't have a lot of luck with this method though as ammo.js tended to explode and crash. Thankfully, the wonderful Schteppe and his Canon.js saved the day. Modeling the strings turned out to be straight forward and one can get the idea across quite easily.

Modelling the larger, static components was an interesting challenge. I stuck decided to use Blender as it's my favorite of all the 3D packages these days. Exporting from Blender to a json format is quite simple (in the future, I'll be using a compressed, binary format instead) and allows easy import into coffeegl. The textures were created, by hand, with the GIMP and the bumpmaps generated with CrazyBump (which I think is still magical!). Going it alone and writing my own WebGL library did incur an initial time penalty but towards the end of the project, it proved to be the right decision, allowing for first changes and updates.

Graphically, the build is fairly simple, using a basic Phong lighting solution, coupled with a bump map and an Anisotropic shader function, to give the lovely brass and polished wood effects. My only regret is not having enough time to photograph the Whipple Museum itself to create a reflection map for the metal sections. Maybe next time. I had used a small amount of SSAO for some extra depth but it turned out to be too costly for the effect to be worthwhile.

One final challenge remained - an installation inside the museum itself. The museum wanted to mount a version next to both Price's and Seb's models. I decided that the best option was to run the site on the Google Nexus 10. Chrome supports WebGL (yay!) and that made it the ideal solution. It did present a few challenges however; the user interaction being the chief concern! Using a mouse and keyboard is quite different to how touch screens work and you certainly aren't given any handy gestures like pinch or two-finger-swipe so one needs to program these in too.

As a computer scientist (or indeed, any scientist) not being able to test or verify is very disconcerting. I am told, by historians, that the notion of a ground-truth is very bad history, which I understand but really dislike. So I set about comparing the equatorie to NASA's Horizons Ephimerides. Using telnet, one can log into the Horizons system and find the positions of all the celestial objects (and satellites!) with a few key presses. Its marvelous! Turns out the Equatorie is really quite accurate.

There are a couple of important and related points to make about this project. Firstly, I did it my way, as the song goes. I'd made the decision to write my own library, setup my own tools (with the help of node.js, browserify and Canon.js) and work how I wanted to work. Part of the reason I do what I do is I get to work how I believe I should work. Agency over one's work is really important, especially these days. It's a piece of work I can stand against and say, yes, this is good. I am happy to show this to anyone and let it stand on it's own merits.

I feel that this is one of the best uses of WebGL. It recreates an object that didn't exist and therefore allows historians to perform more research. Because it's on the Web the public can get a feel for how the device works. The whole thing has a wonderful educational and academic appeal, unlike many of the WebGL sites out there which tend to be either amazing technical pieces at best, or poor advertising at worst.

The second point is that we are obsessed these days with collaboration, sharing, open-source and such. I've never been one for working in large teams of programmers - major players like John Carmack seem to agree. Working with Memo Akten was amazing and I learned so much from him, as a programmer, but this kind of thing is rare. I personally think the best collaborations are ones where people can get support but are allowed to work to their best with their skills and are given the responsibility to see their end done. Seb Falk is an amazing historian who worked really hard on the maths behind the equatorie and respected my opinions on the build and trusted me to get the job done. Its a pleasure to work with people who are experts in their fields and love what they do. Our skills are complimentary but our passion for the project was shared and I think that is the key to good collaboration.

You can see the original manuscript and the new model at The Cambridge Digital Library - Peterhouse Equatorie Manuscript